Page 48:

as Johanne the Bank, made us some fresh coffee. This, in so many ways, signified the end of my apprenticeship. That same morning I had gotten a pint of cream from Trine Hans Jørgens which we had along with our coffee.

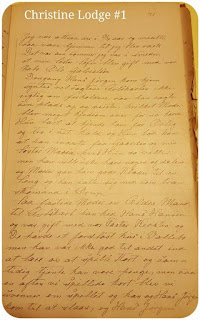

It was around New Years in 1857 when I was all set to be able to place my two feet under my very own table in the form of an apartment of my own. It so happened that H. Jørgen had a shed, which as a matter of fact is the same shed as the one depicted in the drawing of the farm on page one and which is labelled as "spare space." It used to be part of one of the barns and now it was given to me to be used as an apartment. The room was six feet in width and sixteen feet in length. At one ned of the room is where I set up my things which consisted of a bed and my trunk. I crafted a table which was one foot wide and two feet long. I mounted it on the wall directly across from the bed so that I could sit on the edge of the bed while eating at the table. The table was fastened to the wall with leather straps so it was therefore possible to either have the table down or up. When it was down and in use I used to put a piece of wood under it as support. At the other end of the room was where I had my work station which was where I usually had 1 1/2 or 3 foot lengths of clog making wood, along with my chopping block, hollowing block, carving bench, tools and much more. My kitchen

Page 49:

consisted of a small box which sat under the bed. That is , as long as I had remembered to do the dishes and to put everything away.

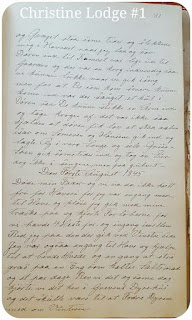

My food consisted of an eight pound loaf of rye bread, a one pound sausage, one pound of cheese as well as receiving a cup of coffee from Trine H. Jørgensen every day at the price of four schilling per day. I lived on this diet for sixteen months, except for one day where I was working for one of the peasants. Two young men who were dancing instructors came to town during this time and I, as well as many of the other young people in the area, signed up for lessons. They covered three towns and offered lessons two nights in each town every week, so they were busy seven days a week.

Myself, as well as several others, went even if they were giving lessons out of town which allowed us to get a rather good grasp on it. The entire course cost us each ten Mark and when we were done with the dancing in the evenings we'd play cards for the rest of the night. Upon completing the course, I came upon a guy named Mads who wanted the two of us to hit the open road as dancing instructors. However, I didn't think that Mads was a very good dancer and I managed to talk myself out of that situation. I can only assume that he chose me because he admired my dancing skills.